Spurred by a mass e-mail to all the world’s Komossas from the farmer Kjell Engström of the Finnish town Komossa, the night photographer sets out on a curious journey through the streaming light of Finnish summer nights.

SZ Online

The Berlin Photographer Jens Komossa only opens the shutter of his camera once night has fallen. Four or five hours can easily slip by before he has the picture he wants.

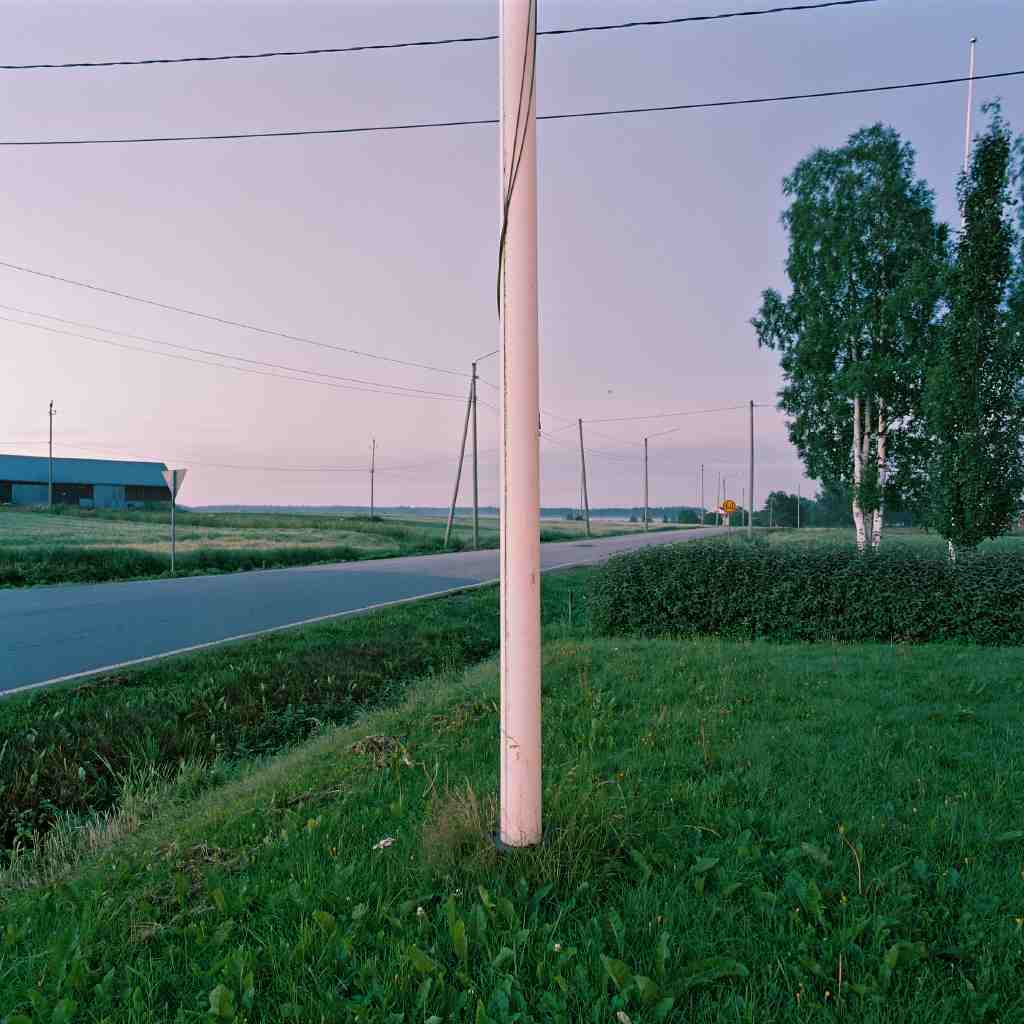

He has spent many nights this way in green, neon-lit French towns, and on the streets of Berlin. Some time ago, Komossa turned the night in Finnish Komossa into day. How quaint: Komossa found himself, thanks to the internet and a farmer by the name of Kjell Engström, pulled to the little village in Osterbotten that happened to be his namesake.

Shortly after making this internet acquaintance, Jens Komossa visited the lonely, 100-person village. On his nightly photo hunts in the natural, open setting, he had strange, never before dreamed-of experiences: “At night, the sun would disappear, but not the light.”

Komossa’s discovery of nearly day-bright, nighttime photography in Komossa seemed to require an equally unusual setting for the exhibition. As of tomorrow, the guests of the mixed sex saunas of the Chemnitz state bathhouses can relax and enjoy the sight of Komossa’s work. The opening is today (5:30 PM), in the sauna.

“Komossa in Finland” is a two-part exhibition of the New Saxon Gallery; another selection of large format, long exposure time photography is on display at the museum itself, “Tietz.” In the meantime, Komossa has learned what Komossa means in Finnish: The cow in the clearing.

Ch. Hamann-Poenisch

The Little Komossa Trip

and the newest stories

In recent times, one has gotten used not only to being deluged with ‘spam’ emails from unknown parties, but also, depending on one’s spam filter, to having real emails mistakenly deleted. One fine day, I received a different kind of email. In few words, the then unknown to me Kjell Engstrom – a strange sounding name to German ears – told me that he came from the small town of Komossa, and wanted to know if, perhaps, I had any relatives there.

Komossa – was this somehow a mistake? Or one of us misunderstanding the other’s English? At this point, it is important to mention that my name is Jens Komossa. Had I understood him correctly? Was this someone who came from a place called Komossa? As per today’s custom, I immediately googled it, and found www.komossa.fi. As I opened the page, I was suddenly met with the vacant stares of several cows, cows I now know belong to Kjell’s neighbor Magnus, at who’s house I have had the pleasure of eating elk, prepared by his painter wife; as it happened, that would be one of many elk experiences I was to have, and had only the day before that dinner been admiring elk antlers.

But we don’t want to get ahead of ourselves. On to the googled picture of Komossa: white writing on a blue sign welcomes visitors to the little town in one picture, while another shows a sweeping overhead view, as from a mountain top or an airplane, of the cozy little village. That was Komossa, or rather, the other version of Komossa, if one can make oneself stop conceiving of Komossas merely as people.

As my friends know well, I’m a far cry from being a prompt answerer of emails. It was therefore sometime before my attention turned back to Kjell Engstrom, as I sank back into the stress of the life of a photographer in Berlin. Some three months later I was invited to a photo exhibition at the state gallery of Chemnitz, and there a thought occurred to me: my art photography is night photography, and at that time of year in Finland, the nights are almost as light as the days. With this in mind, and the coincidence of my newfound personal interest in the town of Komossa, I decided to book passage on a ferry to Finland. I was to be accompanied by the TV journalist Christine Daum, who found this Komossa saga fascinating, and had decided to make a short film documenting it.

Inspired more by feeling than by reason, we decided to go to Finland the ‘Finnish way.’ That is to say, we drove to the fairy crossing at Rostock, crossed with our car to Trellbord in Sweden, and then again to Turku. Unlike in an airplane, where distances vanish and pass unfelt and you are suddenly set down in a new land, when traveling by car you feel the distance, and see the changes around you as they happen. Indeed, the comfortable speed of the car-trip seemed very fitting, as we drifted along the slow, country roads, following the big-rigs along with all the other Finns.

The duration of this road trip made us intimately acquainted with the danger of driving through the Finnish woods: elk. In Germany one expects to have a deer jump out in front of one’s car; in Finland, a different threat lurks. As we arrived in Komossa, the third house proved to be our target, as Kjell stood there in his garden, across the street from the ‘Komossa Skola.’ Next to Kjell were his three sons Thomas, Tommy, and Jonny, on their new trampoline; we couldn’t help but be somewhat jealous of their endless spinning and tumbling.

As I had left Germany, I had thought my Swedish car, camera and telephone would help me meet some minimum standard of Scandinavian-ness I was sure existed, and that I would therefore be welcomed. Kjell and his sons’ kindness immediately showed me the error of my ways. I could have arrived in a Mercedes, Audi, or BMW and these big-hearted people would surely have welcomed us just as warmly.

Finn Tango

From Kjell’s surprise at hearing Finnish tango music in my car, and the brief ensuing conversation about the differences between Finnish and Osterbottish life styles and tango styles, a plan for a trip to the Finnish-occupied part of Finland to try to out-tango the Finnish came to life. News of the plan quickly spread through Komossa, and it became apparent that a bus would be needed to transport the growing crowd of would-be tango dancers to the Finnish sector. Also necessary, of course, was a smooth-talking bus driver to get us in and out of the Finnish sector unscathed.

Kjell took it upon himself to give me a comprehensive, two-minute instruction in three or four of the more fundamental tango dance steps, momentarily turning the living room into a red-hot dance floor. My new group of friends then dutifully gathered around the kitchen table over a glass of whiskey, which turned out to be the most important part of this hasty group lesson.

After further discussion over the rest of the now strategically deployed whiskey bottle- a sort of preemptive disinhibitor- we filled our canteens with more of this battle mixture, cleverly camouflaged with apple juice, and prepared to set off.

Through the kitchen window, tango-hopefuls could be seen descending on the Komossa Skola from all directions, and shortly thereafter they had taken up position in the bus. As we boarded the bus, their wide smiles and warm greetings told us that they had seen to it to make preparations similar to our own. The rest of the team was gathered along the way, and with our numbers now at full strength, we fell into line for the journey to Kalliojarvi.

A new surprise awaited me on the trip to Kalliojarvi: from the enchanting Finnish ladies handbags – which I had presumed contained make-up and accessories – well-chilled beer bottles were conjured up and levered open by the molars of their male companions. Thusly provisioned, we arrived at our target, an immense log-cabin style building on the forest’s edge, ideally situated by a lake: this was Kalliojarvi.

Once our ration of wonder elixir had been partitioned, the group, accounting for fully half of the town of Komossa, set up camp at a table on the patio, and proceeded to enjoy the view or to chat with their neighbors. As I went to relieve the mounting pressure stemming from the surplus beer I had indulged in – an exercise some of my fellow travelers had already carried out on the roadside since our incursion into the Finnish sector – Kjell, our de-facto tour guide, had taken it upon himself to declare this a ladies’-choice dance, and declared a portion of the room our official dance floor. After Henry treated me to a beer, I had the pleasure of dancing with his wife Soile, whom Kjell had aptly described as an exquisite dancer. I am quite certain that I went on to have a wonderful time the enchanting ladies of Komossa on the dance floor, though my memory of the day becomes much less clear from then on. The true sequence of the events that followed can only be speculated upon. Along with reiterating my hope that I did not step on too many toes in my inept attempt to dance tango, I would like one more time to give my heartfelt thanks to all those who shared in that wonderful evening.

Competition of the true Komossa men

In 1986, the two most athletic young men in Komossa, Hilding Back and Karl-Goran Lofgren challenged each other to the first of the now year round shot-put competitions. And while the land of Finland has been slowly rising since the end of the last ice age, the Back family garden seems to have been slowly sinking, beaten down over the years by the constant pounding of the shot-put competition.

Around the original two shot-putters, a small, ever-changing group of other competitors have sprung up. Amazingly, the years of training and the superb physical condition of the “old rabbits” Hilding and Karl-Goran are still more than enough to put to rest any competition offered by younger challengers. The intricate rules, developed over the years, seem to give away another one of the old rabbits’ strategies: that of confusion. The game’s main rule, however, is and shall remain that everyone has a good time together.

Someone let loose a loud cry, signaling the beginning of the match, and the balls begin to fly. I began to try the old schoolboy trick whereby one tries to make oneself invisible, and was initially optimistic at my chances of avoiding having to take a turn. But sure enough, a few awkward minutes later, there I stood behind the heavy wooden beam marking the throwing point, with a 5 kg ball in my hand, about to take part in the ungraceful plowing of the Back family lawn. A piece of tape with my name written on it wrapped around the handle of a screwdriver would mark the limit of my heaving ability. They informed me that next year, a GPS system would replace the screwdrivers, another devious part of their ongoing strategy of confusion, which was to end only when my screwdriver was planted unassumingly somewhere in the middle of the pack. While the group warmed up and the rag-tag bunch of screwdrivers marched slowly forward, it was only with maximal exertion that I could reach my initial mark.

I wonder to this day if coffee is the only thing served in the kitchen next to the make-shift shot-put field, or if their isn’t some house recipe for a performance enhancing mixture of local herbs…